This article was produced as a collaboration between Bolts and Mother Jones.

On a Saturday morning in December 1993, Jimmie Christian Duncan ran to his neighbor’s house and frantically banged on the door, pleading for help. He was holding the limp body of a toddler in his arms. The child, named Haley, belonged to Duncan’s then-girlfriend. The girl’s hair was wet. She wasn’t breathing. And even after one of the neighbors tried CPR, she wouldn’t wake.

Duncan, who goes by Chris, had just turned 25. He had a reputation around Monroe, a small city in rural northeast Louisiana. His penchant for motorcycles and head injuries—from car accidents, dirt bike crashes, bar fights—earned him a nickname: “Deathtrap Duncan.” He fought often with Haley’s mom. But he also had a sweet side: He loved to cook and would let Haley sit on the kitchen counter next to him, testing whatever he made.

As the ambulance arrived, Chris’ distress mounted to such a degree that paramedics asked one of the neighbors to take him outside. The neighbors drove him to the hospital behind the ambulance. As he was waiting for news, Haley’s grandmother showed up and accosted him. “It’s all your fault,” he remembers her shouting.

Trying to defuse the tension, police took him to the police station. When they told Chris that Haley was dead, he became irate and refused to believe them. He told officers he had given the 23-month-old a bath, then left the room to wash some dishes. When he heard a splash and a thud, he ran into the bathroom to find her face down in the tub. In the interrogation room, he just kept repeating three words over and over: “Bring her back.”

Detective Chris Sasser, a 13-year veteran officer working in the West Monroe Police Department, went to investigate. His examination of the house, a drab duplex, seemed to confirm Chris’ account: dishes in the sink, children’s toys floating in a few inches of bathwater. Based on Sasser’s investigation and Chris’ statements, police decided to charge him with negligent homicide.

But later that evening, everything changed. Sasser received a call from Steven Hayne, the Mississippi doctor tasked with the autopsy. Hayne said he and his partner, forensic odontologist Michael West, had conducted a preliminary inspection of Haley’s body. Hayne reported shocking new information: The duo concluded that Haley had likely been sexually assaulted, and they had also noticed indentations speckling the little girl’s body that appeared to be human bite marks.

Hayne’s call kicked the investigation into overdrive. Sasser upgraded the charges against Chris to first-degree murder. The next morning, he had a dentist come into the jail and cast Chris’ teeth, then drove the resulting dental molds to West in Mississippi. West reported a match: Various marks on Haley’s body, he concluded, had a “high correlation” and even a “positive match” with Chris’ teeth.

Chris spent the next four years in the Ouachita Parish jail, insisting on his innocence. In March 1998, his trial finally began. The district attorney, a powerful local figure who courted the spotlight, used language as crude as it was unsparing. During his opening statement, he told the jury, “The doctor’s going to tell you he rode that baby like a bull.” Haley had “screamed and she died in a bathtub full of water so bloody, you couldn’t see the bottom,” he said. “Red with blood.” The young court reporter, early in her career, sat just in front of the jurors. She still remembers the sound of them crying behind her.

The prosecution conjured a story of a demonic sexual frenzy, a cold-blooded decision to cover up the crime by forcibly drowning the child, silencing her for good, then a methodical obviation of the evidence. Because there was no other incriminating physical evidence to be found—no blood, no seminal fluid—the DA hammered on the bite marks, referencing them eight times in his opening statement. Chris’ lawyers tried to counter that nobody who’d examined Haley’s body before it arrived at the Mississippi morgue had noticed anything awry. But there was another damning factor: the testimony of a jailhouse informant who claimed Chris had confessed to him.

The jury deliberated for just under three hours. They prayed together. And they returned their verdict: guilty of murder in the first degree.

The DA’s characteristic bombast didn’t let up during the penalty phase, in which the 12 Ouachita Parish residents were called to decide whether Chris deserved to die. “Doubt?” he said. “There’s no doubt in my mind, your mind, nobody’s mind, he did it.”

On April 9, 1998, the jury sentenced Chris to death.

On March 18 at 6:50 p.m. local time, the state of Louisiana executed 46-year-old Jessie Hoffman Jr. by nitrogen hypoxia. Hoffman, a Black man from New Orleans, spent more than 26 years in Angola, where he grew close to Chris and others as a member of the death row community. Hoffman had become a practicing Buddhist during his time in prison. According to his lawyers, the state’s decision to gas him to death Tuesday represented not just a form of torture, but also a violation of his religious freedom.

Hoffman’s killing marks a profound rupture in Louisiana: The state has not seen another contested execution since 2002. For the past two decades, executions have effectively been dormant, thanks to the glacial pace of litigation challenging the lethal injection procedure, a short supply of the required drugs, and a slight ebb in support for the practice among the state’s voters. “No one was clamoring for an execution,” Samantha Kennedy, executive director of New Orleans’ Promise of Justice Initiative, told me.

Then, in October 2023, Jeff Landry won election as governor of Louisiana. Landry is an ardent death penalty supporter and ally of President Donald Trump. He won a US House seat as part of the Tea Party wave in 2010, and after one term in Washington, he returned to Louisiana, where he served as attorney general from 2016 to 2024.

Since taking office as governor in January 2024, Landry has signed a flurry of bills functionally abolishing parole going forward, granting police greater immunity, and moving all 17-year-olds into the adult criminal system, even those accused of minor crimes. But the symbolic heart of Landry’s “tough on crime” agenda has been his drive to resume state-sponsored killings. In 2018, Landry had criticized then-Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, for not doing enough to jumpstart executions. Once governor, he did not mince words: “Capital punishment is lawful, and we intend to fulfill our legal duty to resume it,” he told legislators at the start of a special legislative session on crime that he called as one of his first official acts as governor.

The session was a blitzkrieg: Over the nine days it met, the Republican-controlled legislature reauthorized execution by electrocution and legalized nitrogen hypoxia. It also passed a “secrecy statute” that shields execution procedures from scrutiny, rendering them easier to carry out and harder to challenge. In February, Landry announced that the state had formalized a protocol for nitrogen killings. Three executions were quickly scheduled back to back in March. Then, nearly as quickly, one was taken off the calendar after it became clear that the prisoner in question hadn’t exhausted his appeals. Another execution scheduled for this month didn’t happen after the 81-year-old who was slated to be killed died of natural causes.

The US Supreme Court has set legal precedent for the fact that “death is different.” Because of the finality of capital punishment, death row cases involve a lengthy appeals process that attempts to ensure that the prisoner’s rights have been upheld—that avenues of potential innocence or procedural violation have been explored, that there is truly no room left for doubt. This appeals process is where mistakes or misconduct leading to wrongful convictions may come to light and where exonerations typically happen. And Louisiana has had a stunning number of death row exonerations—11 since 1993, the year Chris was arrested.

But the governor appears to see these safeguards as something else: roadblocks.

Just before Landry’s election, he publicly criticized part of the post-conviction appeal process— specifically, a new law called Act 104, signed by Edwards, that expanded pathways for prisoners to put forth a claim of innocence. Landry called it a “woke, hug-a-thug” policy, writing: “Once a verdict has been finalized, there are no more ‘get out of jail free’ cards.”

Once Landry was in the governor’s mansion, the legislature followed suit. During the special session on crime, lawmakers limited Act 104 and heaped on additional barriers. They also restructured the public defense board, which oversees representation for people accused of crimes that can carry the death penalty, and handed control of the new board to the governor.

Attorney General Liz Murrill, a close Landry ally, has similarly demonstrated an eagerness to restart executions. After a federal judge paused Hoffman’s execution last week, ruling that the state’s chosen method of execution would violate his constitutional rights, Murrill immediately moved to appeal, paving the way for the 5th Circuit’s decision to overturn the ruling and send Hoffman to his death. Following Hoffman’s execution, Murrill said in a statement that justice had been “delayed for far too long” and told the Associated Press that she expects four people on Louisiana’s death row will be executed this year.

Murill has also taken issue with the appeals process in certain cases. She maintains that at least two other death row prisoners are out of relief options as well, including one man who was briefly granted a new trial only last year. In interviews, she has suggested using both the courts and the legislature to limit post-conviction relief in the future.

“All of these changes are going to make it much, much harder for lawyers for people on death row to keep them out of the execution chamber,” said Bill Quigley, a professor emeritus at Loyola University New Orleans College of Law who has studied Louisiana’s application of the death penalty and worked for years on capital appeals. “People are going to be executed who wouldn’t be executed if the system was really working.”

In 14 months, Landry transformed the state’s criminal legal system. Resuming executions would be his crowning triumph. Now, with the AG’s help, he’s speeding the condemned toward the execution chamber, signaling a willingness to discount the appeals process for future Louisianans along the way. (Neither Landry nor Murrill responded to requests for comment for this article.)

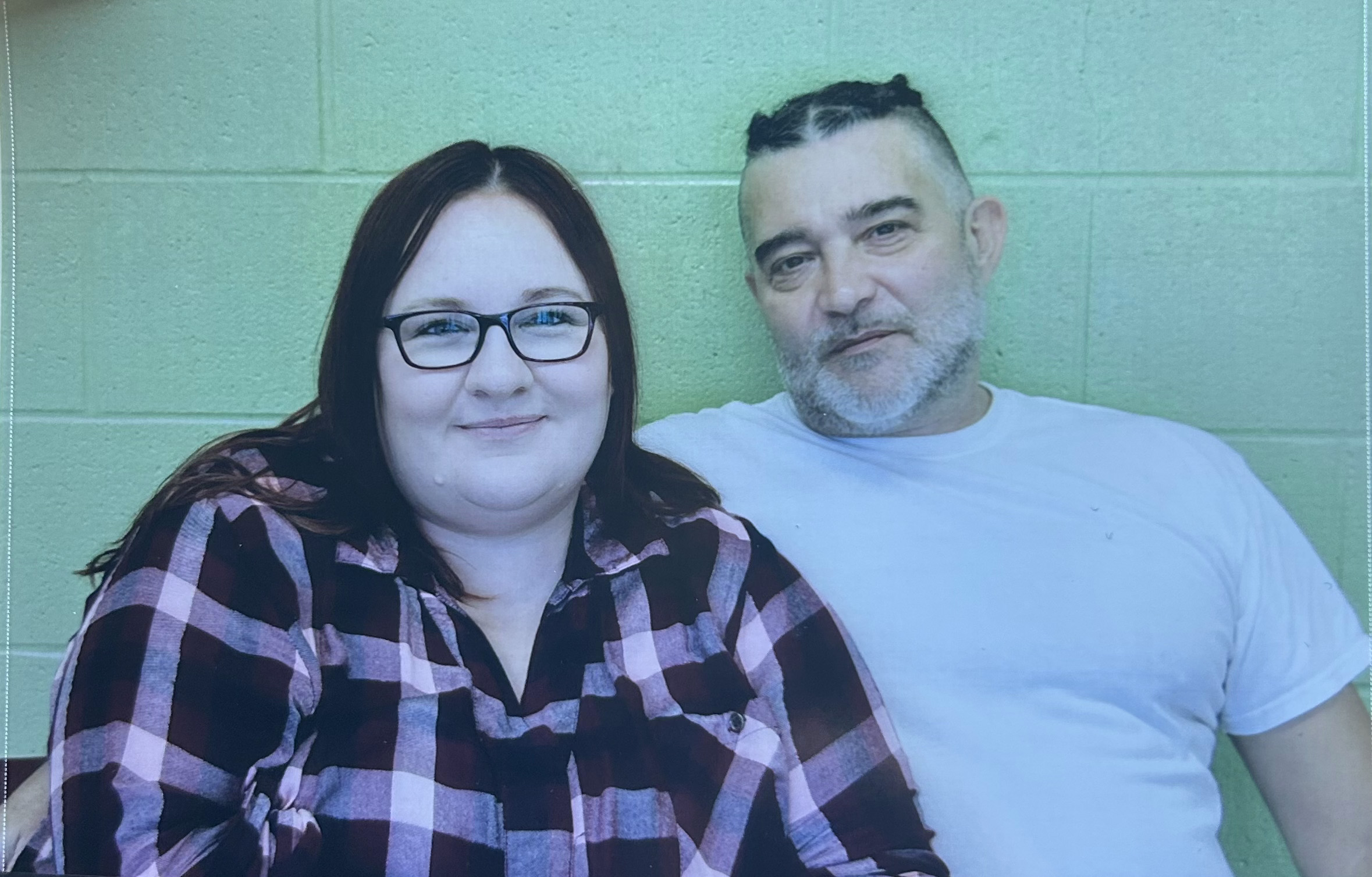

Over 25 years on death row, Chris Duncan has relied on and benefited from the system Landry and his cohort are set to destroy. The many stages of post-conviction relief have been his primary tool in a long quest to prove his claim that Haley’s death was not an act of unthinkable violence, but a tragic accident. Now, as he may finally get another chance to prove his innocence in court, he’s watched the state execute his close friend Hoffman—and ramp up its efforts to put to death other men he’s known for decades. “My fight is a fight for them, too,” he said.

For a long time, Chris left his jail cell when he dreamed. He would wander in the dreams for weeks on end—a sort of furlough of the unconscious. The effect persisted into his days, when respite was scarce.“Even in my waking life,” he said, “I felt that relief of having gone to these places.”

When Chris found Haley motionless in the tub, it felt to him as though the world was ending. Sometimes, he would replay those last moments, holding her in his arms, telling her, “Hang on, hang on,”before letting go of her tiny body for the last time and handing her to the neighbor to perform CPR. He remained shocked by how quickly it had all happened and by the momentum of the state’s case against him. “I just was snatched out of my life,” he told me. “The chances that the truth comes out, it seems nonexistent…you’re just a character in someone else’s story.”

Still, the guilt over Haley’s death consumed him. After more than four years in the parish jail during the trial, it was almost a relief to get a verdict, even though the sentence was death—at least that way he’d get representation for an appeal.

Chris arrived on Angola’s death row in December 1998, one of 83 Louisianans condemned to die that decade, according to the Death Penalty Census Database. The 1990s were a particularly bloodthirsty period in American politics. Prosecutors, judges, and juries sent more people to prison, for longer, than any time prior. In the US, over 3,000 people were sentenced to death and nearly 500 were executed.

Even so, Louisiana operated with particular flair. Clive Stafford Smith, a British attorney who has represented scores of Louisianans in death penalty and wrongful conviction cases, still recalls once walking into court and seeing the prosecutor wearing a necktie with a noose painted on it. “Look, it was a nightmare back then,” he told me.

Neither of Chris’ court-appointed trial lawyers had ever defended someone against the death penalty. (Their training was a single seminar on capital defense.) Court records indicate that their plea to the jury for mercy was lackluster at best. Even after someone is found guilty in a capital case, the jury may still decide to spare them, but a good mitigation argument—one that explores and contextualizes a defendant’s childhood, mental state, and trauma or abuse they’ve endured—is critical. According to Chris’ 2008 petition for post-conviction relief, there was ample material from his past that his original attorneys failed to highlight: his biological mother’s six marriages, including one to a man who beat her while she was pregnant with Chris; his many head injuries; his struggles with drugs. When it came to character witnesses, the lawyers skipped over Chris’ family but called casual acquaintances from his life, as well as former cellmates who simply testified that Chris read the Bible when they were in jail together.

None of this was particularly out of line with the norms of the time. Although prosecutors in Louisiana enjoyed generous funding, in those days, there was a rule that state-appointed defense could spend no more than $1,000 on a given case, all told. “You get what you pay for,” Stafford Smith said. Quigley told me a typical capital defense at the time was “like having heart surgery [done] by an EMT.”

And so this drastic imbalance in resources had predictable results. Even in the most retributive states, only a tiny percentage of people convicted of murder get the death penalty. People tend to think of death row as the “worst of the worst,” but the Louisianans who ended up there—even if they had no claims to be innocent—were very often victims themselves earlier in life. They were almost always very poor, they were disproportionately Black, and many had survived horrific childhoods. Chris had a turbulent youth, but compared to most of the guys around him, he thought himself lucky. There were men there who had suffered abuse and neglect, who were severely mentally ill, who were functionally illiterate. “There’s two things you can’t take out of the system,” Quigley told me. “One is race and the other is money.”

Louisiana’s death row is not only a cross-section of its most marginalized populations, but it also has a staggering rate of wrongful convictions. Between 1976, when the death penalty was reinstated in the US, and 2015, more than 80 percent of people condemned to death in Louisiana eventually had their sentences reversed. “The stakes of life and death are just too high for that,” Quigley said.

The state killed Dobie Gillis Williams, a 38-year-old Black man, in 1999, just over a month after Chris arrived on death row. Williams had met with Sister Helen Prejean, the famous New Orleans nun and anti-death penalty activist, who believed there were enough issues with his case that he should not be executed. The day he was put to death, what shocked Chris the most was how blasé everyone appeared—guards and prisoners alike. To the people around him, he thought, it seemed like just another day. But then again, most of them had been through this before.

By the turn of the 21st century, Louisiana had begun to reevaluate its approach to death penalty cases. The state established general standards for capital representation, created a right to counsel during post-conviction proceedings, and funded organizations dedicated to capital appeals (though money would remain an ongoing battle). When lawyers from these organizations began to take a second look at some of the death row convictions, they found blatant oversights and errors. Stafford Smith took on the case of Shareef Cousin, a young Black man who’d been sent to Angola at 16 for murder. Stafford Smith discovered, among other issues, that the detective investigating the case was the one who called in a tip saying Cousin did it. The Louisiana Supreme Court later overturned the conviction. John Thompson, a Black New Orleanian on the row alongside Chris, was just 30 days from execution when an investigator uncovered evidence of innocence that the DA had withheld from the defense. In 2003, Thompson walked free.

In total, nine people have been let off Louisiana’s death row since Chris arrived there. Three of those cases involved the presence of false or misleading forensic evidence. Every one of them involved official misconduct. “The DAs were cheating to get these convictions,” Kennedy said.

And although it may seem like these exonerations show the system is working, they came only after decades of wrongful incarceration. Jee Park, executive director of the Innocence Project New Orleans, told me she’s haunted by the knowledge that there were probably cases the system didn’t catch before someone was executed. “It’s the unknown—the number of people we don’t know who were killed by the state,” she said.

For Chris, the hardest death to bear was Les Martin, a man who had been like a mentor to him. During their last conversation, he couldn’t bring himself to tell Martin goodbye. “I didn’t stand there with this story of I’m never going to see you again,” he said. “I just embraced him, let him know I appreciated all I learned from him, and I hoped to see him in a few days.”

Martin was executed May 10, 2002. He was 35 years old.

Chris itched watching as other men convicted before him walked free. Every time he thought about the “false reality” the state had imposed on him, he got wound up, his heartbeat racing. At some point, he realized that his obsession was eating him alive. But there was little else to focus on. For years, the men were kept in solitary confinement 23 hours a day.

Chris had spent childhood summers at a swamp near an old forest left miraculously untouched by the incursions of logging companies. There were cypress trees and oaks as tall as buildings with ropes of Spanish moss hanging down—nature’s cathedral, he called it. He guessed that almost no one besides him, his grandfather, and a few uncles had ever laid eyes on those trees. In quiet moments in his cell, he dreamt about wandering out into the bayou and finding a fallen limb to lie back on and listen to the sounds of wildlife reverberate around him. He thought about holidays with his family: multiple generations all crowded around, the women churning out delicious cakes and pies. But the more he ran it back in his mind, the more he realized how far away this world had become. What was real was Angola: the cinder-block walls around him; the bark of the guards; the metallic clang of the doors; and, somewhere off in the distance, the execution chamber.

At some point, he mostly stopped hoping. After more than a decade of incarceration, “everything that you could say was Chris Duncan didn’t exist except for a body in a cage anymore,” he told me. Often, he felt like execution might be an act of mercy.

Back in 2001, Chris had lost his direct appeal to the Louisiana Supreme Court, the automatic first step in the lengthy appeal process that must be exhausted before execution. But in late 2007, Chris was assigned lawyers to work on his post-conviction review—the next stage in the process. The new legal team began digging into boxes and boxes of files: all the DA’s and the original defense attorneys’ papers from the investigation and trial. They met with Chris at Angola regularly, and he tried to share with them everything he could think of that might be helpful for their search.

One day, the lawyers turned up a VHS tape in the files. It turned out to be a recording of Haley’s autopsy made by Michael West, the forensic odontologist whose observations about the bite marks helped lead police to upgrade the charges against Chris to first-degree murder. The video had never been shown at trial. After the state initially tried to withhold it, Chris’ trial attorneys objected, and it was eventually handed over. But for some reason, the attorneys never tried to present it to the jury.

When the post-conviction lawyers played the VHS tape, they were horrified.

At the beginning of the recording, Haley’s body lies peacefully on a table. Her face, virtually unblemished, has a serene expression, almost like she’s asleep. There’s a jump in the video, and West gets started with his analysis. He’s filming himself holding the mold of Chris’ teeth and matching it to different areas of Haley’s body. He doesn’t just compare it, though. He pushes the mold against her body, stretching and scraping it over her skin. And he does it over and over again—over 50 times in a nine-minute span. West is ostensibly using a technique that he personally developed, called “direct comparison.” But it doesn’t look at all like he’s simply checking the mold against marks that are already there. It looks like he’s using Chris’ mold to create those marks himself.

The original forensic odontologist expert for the defense, the legal team realized, had never seen this video. Neither had the forensic odontologist who testified for the prosecution at trial that the marks on Haley were human bites. They only ever saw photos of her body after West was through with it.

In 1993, when Steven Hayne, the doctor who conducted the autopsy on Haley, first brought West in to review what he said were bite marks he’d seen on the girl’s body, both men were well-regarded medical professionals hoping to expand their business from Mississippi into Louisiana. Bite mark evidence was a burgeoning subfield of forensic science; matching had been employed to great fanfare in Ted Bundy’s murder trial. Pioneering dentists in the field raised their profiles by evangelizing the practice.

By the time the video emerged, though, that had begun to change. West’s reputation had already curdled by the time of Chris’ trial in 1998, when the prosecution elected to present a different forensic odontologist as its expert. West frequently made preposterous claims about his expertise and peddled methods that strained credulity. After multiple professional complaints—filed, incidentally, by one of Chris’ lawyers on behalf of his other clients—and various media exposés, West was suspended or forced to resign from several major forensic odontologist organizations.

Hayne faced similar scrutiny. In October 2007, investigative journalist Radley Balko wrote a piece for Reason tearing apart the doctor’s track record. It came on the heels of another story he’d written looking into West’s involvement in a Mississippi case very similar to Chris’: the alleged rape and murder of a little girl, bite marks, a video hidden from the jury. In these investigations, Balko describes Hayne and West as expert witnesses willing to produce conclusions that were favorable to prosecutors but completely devoid of scientific rigor. Balko wrote that one of West’s pet phrases was “indeed and without a doubt.”

The following year, the man at the center of the Mississippi bite mark case was exonerated—along with another Black Mississippian convicted based on Hayne and West’s work.

It wasn’t just Hayne and West, though: Bite mark analysis itself was being debunked. As of last year, Balko told me, “every single scientific body to evaluate the merit of bite mark analysis has said there’s no scientific merit to it whatsoever.” During a 2012 deposition, even West changed his tune, saying, “I no longer believe in bite mark analysis. I don’t think it should be used in court,” though he would later continue to defend the practice in media interviews. Today, it routinely gets dismissed as junk science.

“This bite mark stuff—it’s, I think the legal term is total bullshit,” Stafford Smith said.

But the courts have not kept up with this evolution in scientific consensus, what Balko calls a “direct contradiction between what science says and what the law says.”

Chris’ post-conviction lawyers didn’t know much of this back when they found the video, but they felt certain that it clearly depicted West engaging in malfeasance. It was a seismic turn of events.

Under further scrutiny, other core elements of the case seemed to unravel. The legal team found documents in the DA’s files undermining the jailhouse snitch’s testimony—ones that had never been turned over to the defense. When they tracked down another man who’d been in the same cell with Chris that day, he said he only remembered Chris sobbing and repeatedly professing his innocence.

These revelations had a profound effect on Chris; slowly, he began to emerge from the depths of his depression. At some point, the dreams in which he’d float away from the prison ceased. He realized he didn’t need them anymore.

At the end of 2008, Chris’ legal team filed a roughly 300-page petition for post-conviction relief. The following spring, Balko published a long article for Reason about the case. The article included the West autopsy tape. “To me, that video is incredibly damning,” Balko told me. In early 2009, the National Academy of Sciences published a watershed report on forensics that questioned the scientific validity of bite mark evidence. (Hayne died in 2020. West did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this article.)

For the first time, it seemed like Chris’ fortunes might be shifting, but the process was agonizingly slowgoing. Balko would keep writing pieces, methodically debunking Hayne and West’s methods and investigating their other questionable cases, eventually co-authoring a book on the duo. At least 11 other prisoners condemned on the basis of West and Hayne’s work and testimony would be exonerated or have charges against them dropped. Dozens of other exonerations of people convicted based on bite mark evidence would follow, too. On Chris’ end, there were a few hearings, another early-morning drive from Angola up to a courthouse. And then—nothing. It was almost worse, he felt, than the years when only his friends and family believed in his innocence. Now, he said, it felt like “the whole world knows, but you still wake up every day in prison.”

Scott Greene, a corporate attorney in Atlanta who came onto the case as pro bono counsel, told me that the attorneys continued to discover “jaw-dropping” details that undermined the validity of Chris’ original conviction over the next several years. “We kept shaking our heads: How can all these things have happened in one man’s case? This is incredible!” he told me. “And Chris had been trying to tell us that from day one.”

In 2018, after decades in solitary confinement, the men on Angola’s death row were granted more freedom of movement inside. Along with several others, Chris began attending a weekly prison ministry. He had never liked school, but now he became a registered academic tutor and started teaching classes three times a week. “You never had time to find out who you lined up with spiritually, who you lined up with philosophically—until they opened the doors,” he told me.

During this same period, Louisiana’s criminal justice system was undergoing a significant evolution. In 2017, the state enacted a landmark package of reforms intended to strip it of its dubious distinction as the “prison capital” of the world. The bills were championed by Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards, but they passed with bipartisan support, leading to a 24 percent drop in overall incarceration within five years. In 2021, Edwards signed Act 104, the law that dramatically expanded eligibility for factual innocence claims, including for those on death row.

By this point, Chris had yet another team of lawyers. This legislative change meant that they could now construct an argument around new revelations about Hayne and West’s conduct, the latest scientific consensus on bite mark analysis, and other advances in forensic understanding that undermined the rape allegations. It was a huge breakthrough.

The attorneys filed their factual innocence petition at the end of 2022. A few months later, something unexpected happened: With less than 10 months to go before the end of his final term, Edwards announced that he opposed the death penalty, as he couldn’t square it with his Catholic faith. Sensing a rare opportunity, and acutely aware that Republican Jeff Landry was likely to win the election come October, Louisiana’s capital defense lawyers sprang into action. In June, they filed clemency petitions to the Louisiana Board of Pardons on behalf of 56 of the 57 people on death row, including Chris.

“The 56 people that are on death row are there because of a broken system,” Jim Boren, a longtime defense attorney and former president of the Louisiana Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, told a local radio station. “Eighty percent of the people convicted of death have been exonerated or their cases reversed. So we have an 80 percent error rate.”

Behind the scenes, the men on death row grappled with conflicting emotions. Some were initially reluctant to seek clemency: Life without parole felt like cold comfort when they believed they deserved a new trial. And some of the men beseeched their lawyers to prioritize the cases of Jessie Hoffman and Chris Sepulvado, who were first on the list to be executed.

But Landry, then attorney general, issued an opinion and filed a lawsuit seeking to prevent the pardon board from considering the clemency petitions. The move would stop them from ever reaching Edwards’ desk. A few prisoners got administrative hearings, a perfunctory first step that nevertheless yielded astonishing testimony. Speaking on behalf of one long-term death row resident, a close friend of Chris’, one former death row guard wrote the board that he had so much confidence in the man that “I would move him into my home with my wife and children.” But over and over again, the board voted to deny a full hearing. In October, with just over a third of registered voters showing up at the polls, Landry was elected handily.

With Landry in office, the prospect of mass clemency was all but dead. But the same issues as before—shoddy lawyering, prosecutorial misconduct, bogus forensics—were still cropping up and undermining convictions. In May 2024, Chris was granted a new evidentiary hearing. A judge would evaluate whether the factual innocence petition his lawyers had presented possessed enough evidence to merit a new trial. It would be the first real momentum his case had in more than 13 years.

The hearing was set for late September. It would coincide with a grim milestone: For the first time in decades, five executions were being carried out around the country in a seven-day span. In Missouri, Marcellus Williams would be executed for crimes that he always maintained he did not commit. Alabama would put Alan Miller to death using nitrogen gas—an omen of Louisiana’s future now that Landry was in charge.

Last spring, a longtime lawyer who volunteers at Angola told me that watching the men he worked with weekly go to the execution chamber would be too much to bear. But he harbored no illusions about Landry. “This man we have right now, you’re gonna need a freight train to stop him,” he said.

Back in Chris’ hometown of Monroe, not much had changed but time. The same court reporter who’d been on the original trial as a novice was reprising her role covering this new hearing, now an unflappable veteran. She remembered from the trial that she and Chris were essentially the same age, and she was startled by how much older he looked when they brought him in—his face lined and tired, his black hair shot through with gray. “I guess I’m 30 years older, too,” she told me.

The goal of the hearing was to determine whether Chris had amassed enough new evidence of his innocence since the initial trial to merit an entirely new one. His lawyers, now including Scott Greene, had lined up a crop of expert witnesses to testify about everything from Hayne and West’s misconduct to the discrediting of bite mark evidence and the original lawyers’ inability to mount an effective defense. One witness, a former president of the American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO), lost his faith following the landmark 2009 National Academy of Sciences report, which led him to co-run a study in which dozens of ABFO-certified bite mark analysts reviewed 100 cases and were largely unable to agree on what could be identified as a human bite mark. For him, the results were “devastating,” and he resigned from the ABFO soon after. “It’s a fraud,” he told the judge. Another forensic odontologist spoke of seeing the West video for the first time: “I was astounded, and not in a good way.”

On the first morning in court, one of Chris’ attorneys approached the bench to hand the judge the original VHS tape of the now-infamous West bite mark analysis—which Chris had still never seen. The appearance of the tape had an almost talismanic effect. A few members of Haley’s parents’ families were in court for the hearing, and one, a burly man with a “We the People” tattoo, reflexively drew his arm around his wife. Chris dropped his head, covering his brow with his hands. As the video played in court, showing West pressing the mold of Chris’ teeth over and over into the little girl’s body, he felt violently ill. “Those images are part of an ongoing nightmare,” he told me later. “This girl was precious.”

“Mr. Duncan is the last victim of Dr. Hayne and Dr. West on death row across the country,” Greene told the judge. If the jury had seen the video back in 1998, he wondered, “Would one juror have found reasonable doubt? Unquestionably.”

The hearing lasted six days, and after that, the only thing to do was wait. The judge was expected to hand down his decision within months of the hearing, but as of the date this article was published, no decision has been issued.

In November, Chris turned 56, marking the 31st birthday he had spent incarcerated and another day in limbo between two possible futures. In the one in which he gets a new trial, his lawyers intend to prove his innocence once and for all; at some point in the future, he could walk out of Angola’s gates an exonerated man. “I plan to be set free,” he told me.

But if the judge rules against Chris, he remains on the path toward death at the hands of the state. He hasn’t yet exhausted his post-conviction appeals, but every passing day underscores the reality of execution as Landry pushes to carry out death sentences—none more so than March 18, the day the state killed his friend Jessie Hoffman.

Even getting to this point—the opportunity for a showdown over the West video and the scientific validity of bite mark evidence—was possible because of policy changes made during a different era of Louisiana politics. But it is Landry’s state now. The governor, along with the new attorney general and a willing legislature, seems determined to craft a future for Louisiana in which people condemned by the state to die remain trapped, with little to no chance at relief. “It’s clearly an attempt to go back in time,” Quigley, the Loyola professor emeritus, told me.

In an oversight hearing of a state Senate judiciary committee last fall, one legislator pointed out that they had the power to repeal post-conviction relief entirely—which the AG called “a matter of legislative grace” rather than a right. Some legislators discussed their belief that people getting out of prison due to technicalities brought up in post-conviction appeals were not truly innocent. But it is those very “technicalities”—pervasive racial bias, prosecutorial misconduct, woefully deficient legal representation, the longtime use of nonunanimous juries—that have led to scores of unjust convictions in Louisiana, if not outright wrongful ones.

Chris has spent more than half his life incarcerated for something he has maintained never happened, with the state hellbent on defending the integrity of his conviction. In the Louisiana Landry desires, Chris might never have gotten the chance to argue his case. He might not be here at all.