To say a movie scene or performance gives us chills evokes something common, especially when we’re talking about a horror film, which “Sinners” is, according to the genre’s most basic definition. Rarer still are moments on par with what director and writer Ryan Coogler conjures at that movie’s spiritual peak, where music, dance, cultural reverence and natural sorcery coalesce.

If you’ve watched “Sinners,” you know which scene I’m talking about. (If you haven’t, stop reading this story right now.) The most accurate description I’ve seen in online forums captures its primal radiance: They call it the movie’s “holy s**t” moment.

In the way of all provocative works of art, the subtext of a story is where the treasure is.

It is exalted and sweaty, uplifted and earthy; it is many things at once. The scene is a stunning introduction to Miles Caton’s prodigious abilities, both as an actor playing the movie’s burgeoning Delta blues guitarist Sammie Moore, and as a musician. That man can play, alchemizing melody into a presence that brings together tribes from across time and space. All the while, the cinematography captures the sensation of floating on “the veil between life and death,” gazing down at the past and future coming together to party.

That glimpse of heaven on Earth also establishes the stakes, no pun intended. Once the notes die out, the vampires appear — first to mimic the living’s glory, then to claim their distinct power for themselves.

In the way of all provocative works of art, the subtext of a story is where the treasure is. A halftime Super Bowl performance can be a rap concert by a Pulitzer Prize-winner with a massive hit, or “a diss track to America,” as poet Tiana Clark described Kendrick Lamar’s Feb. 9 performance in the New York Times. Either way, the audience tuned in to Lamar’s signal with a curiosity that inspired conversation for days.

“Sinners” may have people talking for weeks about what it’s supposed to mean, and what it means to them. Its runaway success is a product of feeling and meticulous messaging, some of it hiding in plain sight.

Take the title’s smirk at the idea of piety, and the way the script implicitly questions the legitimacy of that label. The story’s heroes are bootleggers named Smoke and Stack (Michael B. Jordan, in a dual performance), World War I veterans who struck out to find their fortune in Chicago only to return home to the Jim Crow South, and the devil they know.

You may recognize its reference to what’s been called the nation’s original sin and its primacy in 1932 Clarksdale, Mississippi, where the story takes place.

In the main, though, Coogler created “Sinners” as a celebration of the motivating joy, genius and fury of American Blackness in the face of trauma, and that is the siren call pulling people to multiplexes, sometimes twice or more. “Sinners” is culture vulture bait, laden with multiple meanings and dog-eared history pages, and who can resist a puzzle? Even within this lurks a subversiveness, since “Sinners” points to chronicles informing how we’ve arrived at this version of our present that those working to re-establish segregation want to bury or erase.

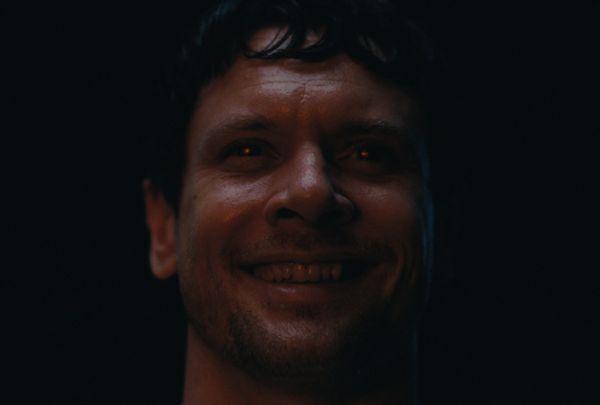

Miles Caton as Sammie Moore in “Sinners” (Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures). Only this time, the threat isn’t wearing white hoods when they appear on our doorsteps. They sport toothy smiles and play Black music just fine, hitting every note correctly. And they want nothing more than to make everyone equal, which is to say, just like them. Because that’s what vampires do.

Reading “Sinners” as an allegory of cultural assimilation and appropriation is obvious, and it’s also simple enough to get a variety of folks to walk through the door. Of course, it operates perfectly well as a straight monster story, too.

But the expanding, deepening discourse surrounding the theatrical blockbuster invites us to do a little homework, if only to better enjoy the music.

Reading “Sinners” as an allegory of cultural assimilation and appropriation is obvious, and it’s also simple enough to get a variety of folks to walk through the door.

Coogler’s Mississippi Delta is ripe with beauty and painful memories. Cotton fields carpet the land to the horizon, and Black sharecroppers labor just beyond the shadow of enslavement, subsisting on scrip that can’t be spent outside the plantations where they live and work, ensuring they’ll never build wealth. This is where Smoke left his long-estranged love Annie (Wunmi Mosaku), a root worker in the tradition of African shamans, channeling Earthly magic for the community’s healing and protection. Meanwhile, Stack is confronted by his ex-girlfriend Mary (Hailee Steinfeld) whom he somehow persuaded to pass for white, leaving her people behind, which she was never keen to do.

Mary isn’t the only person in Smoke and Stack’s extended family with one foot in the Black world and the other foot in the white one. They have a working relationship with Grace (Li Jun Li) and Bo Chow (Yao), Chinese-American grocers who do business on both sides of the color line, including patching up any injuries the two might cause.

Hailee Steinfeld as Mary in “Sinners” (Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures)Even within these hardscrabble circumstances, magic abides. The twins return to Clarksdale to open their own dance hall, Club Juke — a den of sin, to the church folk. Annie’s voiceover during the movie’s cold open tells another story, about special people “born the gift of making music so true that it can pierce the veil between life and death, conjuring spirits from the past and the future.” This talent has the power to heal, we’re told, but it can also draw evil — it’s holy s**t, she’s saying.

Hailee Steinfeld as Mary in “Sinners” (Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures)Even within these hardscrabble circumstances, magic abides. The twins return to Clarksdale to open their own dance hall, Club Juke — a den of sin, to the church folk. Annie’s voiceover during the movie’s cold open tells another story, about special people “born the gift of making music so true that it can pierce the veil between life and death, conjuring spirits from the past and the future.” This talent has the power to heal, we’re told, but it can also draw evil — it’s holy s**t, she’s saying.

Caton’s Sammie is one of those beings. The Mississippi Delta is the domain of the greats — Charlie Patton, Robert Johnson and local legends like Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo). Sammie, who adopts the stage name of Preacher Boy, is set on joining that pantheon, which Stack invites him to do by performing at Club Juke.

Sammie plays powerfully enough to touch that bridge between past, present and future that Annie spoke of. Caton’s molten voice makes that impossibility feel real. Once Coogler and cinematographer Autumn Cheyenne Durald Arkapaw add their creativity and instruments to the melody, however, we’re treated to a cosmic vision.

As Sammie croons, he’s joined by an electric guitarist playing like Jimi Hendrix but dressed like a member of Parliament-Funkadelic. Then the camera whirls to capture a turntablist and rapper wearing a Kangol bucket hat. African dancers surround Sammie, while women twerk and men Crip dance in different sections of the dancefloor. And this experience isn’t culturally exclusive. When Grace and Bo Chow join in, a Xiqu dancer (from traditional Chinese opera) whirls nearby.

Like Delta Slim tells Sammie before his music links up with eternity, what they do is sacred; it is magic, and it is big. As Coogler proves with that signature scene, anyone can access that power. The only prerequisite is being alive and welcoming all versions in their natural purity.

Not long after Sammie returns us to Earth, the contrast to this dream state shows up at the juke joint’s door — three white strangers asking to join the party. Their leader, Remmick (Jack O’Connell), introduces himself and his companions, Joan and Bert (Lola Kirke and Peter Dreimanis), and claims to believe in equality. All they want to do, he says, is play music together.

Jack O’Connell as Remmick in “Sinners” (Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures)On cue, Remmick produces a banjo and launches into an arrangement of “Pick Poor Robin Clean” — popularized at that time by a Black woman, Geeshie Wiley — that Pat Boone would have envied for its corniness. It is purposely comical, and explains why Smoke denies them entry aside from their potential endangerment to their other patrons. All it takes is one misunderstanding between a member of this trio and someone inside to stir up a lynch mob.

Jack O’Connell as Remmick in “Sinners” (Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures)On cue, Remmick produces a banjo and launches into an arrangement of “Pick Poor Robin Clean” — popularized at that time by a Black woman, Geeshie Wiley — that Pat Boone would have envied for its corniness. It is purposely comical, and explains why Smoke denies them entry aside from their potential endangerment to their other patrons. All it takes is one misunderstanding between a member of this trio and someone inside to stir up a lynch mob.

Smoke’s instincts are right, but not for the visible reasons. We know Remmick doesn’t want to join the celebration. He wants to run it.

Where other vampires drain their victims’ blood, Remmick absorbs their memories and abilities, including their language and their magic. As Annie describes it, the victims’ souls are trapped. And that’s why Preacher Boy’s talent draws Remmick. He wants to connect to his ancestors, not the ancestors. That’s the difference.

In the two weeks since its opening, “Sinners” has become the fifth highest-grossing film worldwide this year so far, with the third highest domestic gross, according to Box Office Mojo. Its second-weekend sales decreased a mere 6%, the smallest second-weekend drop of any movie since 2009’s “Avatar.”

That success proves the market viability of original ideas and perhaps a willingness to engage in honest (if fleeting) discussions about the ways America’s tortured past haunts our present. But we already knew that to be the case; the Super Bowl wasn’t too long ago. Remember what Lamar did there? It was simple on its face, a medley of new and old hits leading up to his performance of “Not Like Us.” There was no distinctive bone-breaking choreography, no show-halting costumes or props.

The story of American music is really the story of Black music, especially the blues.

We should say, there was none of that if you didn’t know how to read Lamar’s stadium-sized messaging: the aerial shots of lighted gaming console icons; red, white and blue-clad dancers arranged to look like an American flag pulling together and falling apart; the interjections by Samuel L. Jackson as Uncle Sam playing Uncle Tom playing Uncle Ruckus. The imagery tells the story of a rigged game while Lamar’s lyrics confront the violence visited on, and America’s unkept promises to, the Black folks who built this country. “Forty acres and a mule, this is bigger than the music,” he rapped. ”Yeah, they tried to rig the game, but you can’t fake influence.”

Lamar’s performance received 125 complaints to the Federal Communications Commission, most of which fell into the “it was too Black” basket: “There wasn’t one white person in the whole show,” one of them read, as relayed by Billboard. “They get away with it, but if it was all white, it would be a different story . . . This was a disgrace, and it gets worse every year.” It also became the most-watched Super Bowl Halftime Show in history, drawing some 133.5 million viewers.

“Lemonade,” Beyoncé’s video album released nearly a decade ago, can be appreciated as a musical masterpiece with an atmospheric video accompaniment. Combing the lyrics for clues substantiating Jay-Z’s infidelities became a popular hobby that spring, too. Remember when everyone obsessed over the identity of “Becky with the good hair”?

Black folks, and Black women especially, recognized certain homages on sight: the recurring suggestions of Yoruba deities, the purposeful insertion of certain Black stars in specific scenes, the tributes to mothers living and ancestral. Those deep nods were for us. Respecting that doesn’t preclude anyone from learning about what Beyoncé intended by stitching them throughout her work.

Yet it was common for white women to claim Beyoncé made “Lemonade” for all women, which, fine. All green money spends here. By that logic, anyone can wear cornrows, too. It takes a willingness to understand and honor the hairstyle’s origins and what that plaiting symbolizes to accept that not everybody should flaunt it.

This adds another subliminal layer to Coogler and his musical collaborator Ludwig Göransson’s choice to have Remmick cover “Pick Poor Robin Clean.”

Discussing race and cultural appropriation attracts the predictable insistence that we’re “seeing things,” that the malice we notice lurking behind innocuous-seeming language is imaginary.

The story of American music is really the story of Black music, especially the blues. This lesson is embedded in the official “Sinners” Spotify playlist curated by Göransson and Coogler, which travels from the soundtrack to the earliest Delta blues recordings through B.B. King’s and Muddy Waters’ greatest hits, eventually landing in a run of songs by Alice in Chains, Metallica and Young Dolph. There are Gaelic songs on the list too, including a tune by the Dubliners, none of which feels out of place or ruins the flow. It all belongs, in the same way the crash of Chinese cymbals in the remix of Sammie’s signature song “I Lied to You” only punches up that gumbo’s flavor.

That song was designed to move the audience, but it’s O’Connell’s soulless spectacle via “Pick Poor Robin Clean” that’s become a disturbing earworm.

Why Remmick’s song choice is so disquieting isn’t apparent, aside from the odd juxtaposition between the lyrics and his jaunty cheerfulness:

I picked poor Robin clean, picked poor Robin clean

I picked his head, I picked his feet

I woulda picked his body, but it wasn’t fit to eat

Oh, I picked poor Robin clean, picked poor Robin clean

And I’ll be satisfied having a family

Then again, sufficient bother tends to make us seek answers. Some interpretations say it’s a song about gambling, supported by Wiley and fellow musician L.V. Thomas’ conversational exchange about “trying to play these boys the new cock robin” – a cock robin reportedly being old English slang for “someone who’s easily persuaded to follow the will of another.” You don’t even have to pull that many strings on the conspiracy wall to suss out the plainer insult of Remmick and his white accompaniment unleashing a country-fried version of an arrangement by a Black woman to ingratiate himself to the oppressed folks he wants to devour,

“Can’t we just, for one night, just all be family?” he pleads, a bit too hungrily. But nobody wants Remmick at this fish fry, and the rules of vampirism, and the Culture, explain why he can’t force his way in. He must be invited.

Want great food writing and recipes? Subscribe to Salon Food’s newsletter, The Bite.

Coogler’s choice to make the head vampire Irish is specific while not being denigratory. This is clearest in his and Göransson’s inclusion of “Rocky Road to Dublin.” This Irish standard sings of a country boy who goes to Dublin to make his fortune, only to be robbed, then takes a ship to Liverpool, where he’s rejected and beaten. Remmick performs it in a field close enough for the survivors inside Club Juke to hear it, but not to see what he’s done with his victims. And O’Connell punches it into a banger, without question, calling forth an electricity that can only come from one man’s blood memory, Remmick’s.

The newly undead Mississippi folks dance along, but it’s different from Sammie’s juke joint rapture — unnatural and jerky, even as they keep the rhythm. This is not their dance but Remmick’s — he’s compelling them to dance his way.

But then, that move isn’t unique to one monster and certainly not to one people. It’s older than America, older than vampirism. It is the midnight blues of the human condition.

Discussing race and cultural appropriation attracts the predictable insistence that we’re “seeing things,” that the malice we notice lurking behind innocuous-seeming language is imaginary. A similar introduction of disbelief plays out across the horror genre, where someone glimpses the threat or the true deadly nature of the masked monster, only to have their fears doubted or dismissed.

In this respect, “Sinners” validates us, letting us know it’s OK to consider the notes playing within the surface melody and embrace the minor keys while comprehending that they sound ominous for a reason. Our struggle to survive until a new dawn breaks can only succeed by making room for everyone’s variety, both ancestral and present. That’s where the magic has always been.

“Sinners” is playing now in theaters.

Read more

about this topic