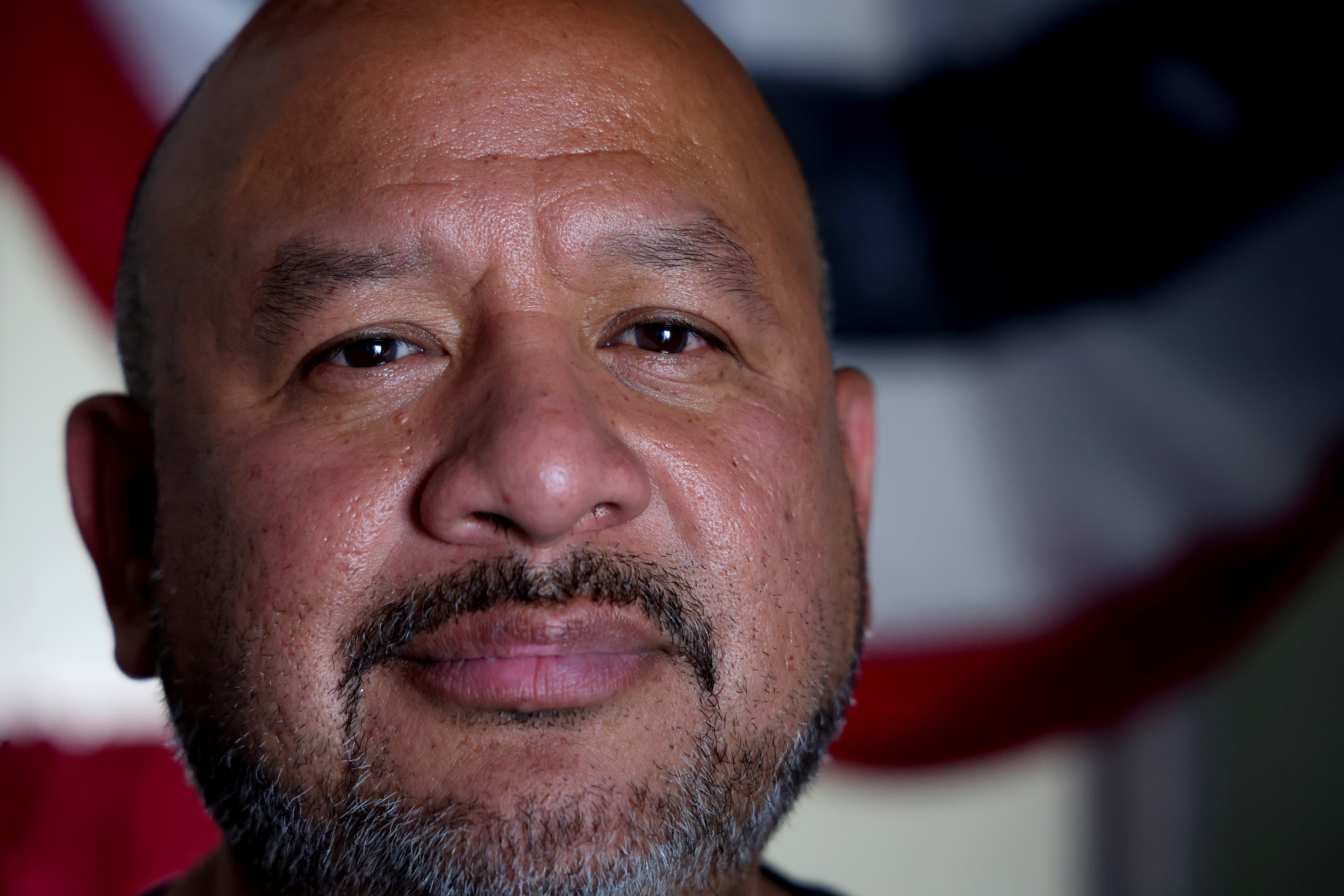

Army veteran Jose Francisco Lopez holds a portrait from his time in service on Saturday, June 28, 2025, at the Deported Veterans Support House in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Lopez opened the home in 2017 to help veterans deported from the U.S., despite their service to the country.

In the months leading up to the 2024 presidential election, US Army veteran Sae Joon Park kept in mind a warning from an immigration officer: If Donald Trump were elected, Park would likely be at risk for deportation.

Park was just 7 when he came to the US from Seoul, South Korea. A green card holder, he joined the Army at 19 “to serve the country that I believed in,” he said. He received a Purple Heart after being shot twice while deployed in Panama, but after leaving the military, he lived with PTSD. That led to an addiction to crack cocaine and, ultimately, trouble with the law.

In 2009, he was arrested for drug possession. After he jumped bail, afraid he would fail a drug test, he served time in prison and was told he would be deported. However, because he was a veteran, he was granted deferred action upon his release, which allowed him to remain in the US as long as he checked in with immigration officials annually.

For 14 years, he did just that while raising children and building a new life in Honolulu. In June, everything changed.

When Park went in for his regular appointment, he was told he had a removal order against him. After talking things over with his family and lawyer, he decided to self-deport because, he said, he worried he could not survive extended time in detention while fighting deportation.

“I could have ended up in ‘Alligator Alcatraz,’” Park said, referring to the Florida detention center that has come under fire for alleged inhumane conditions. “I was a legal resident. They allowed me to join, serve the country—front line, taking bullets for this country. That should mean something.”

Instead, he said, “This is how veterans are being treated.”

During his first term in office, Trump enacted immigration policies aimed at a group normally safe from scrutiny: noncitizens who serve in the US military. His administration sought to restrict typical avenues for immigrant service members to obtain citizenship and make it harder for green card holders to enlist—actions that ultimately were unsuccessful.

Now, as the second Trump administration engages in a campaign to detain and deport immigrants living in the US, military experts and veterans say service members are once again targets.

“President Trump campaigned on a promise of mass deportations, and he didn’t exempt military members, veterans and their families,” said retired Lt. Col. Margaret Stock, a lawyer who helps veterans facing deportation. “It harms military recruiting, military readiness and the national security of our country.”

Under the Biden administration, Immigration and Customs Enforcement issued a policy stating a noncitizen’s prior military service was a “significant mitigating factor” that must be considered in enforcement decisions, including deportation orders. The policy also offered protection to noncitizen family members of veterans or those on active duty.

In April, under the Trump administration, that policy was rescinded and replaced with one saying that while “ICE values the contributions of all those who have served in the US military … military service alone does not automatically exempt” one from enforcement actions.

The new policy directs agents to ask about military service during intake interviews and to document service. However, local ICE leaders have the authority to proceed with deportations of those who have served, though they may consider factors such as community ties and employment history.

Both policies barred enforcement actions against active-duty service members, absent significant aggravating factors. Under the new policy, noncitizen relatives of service members are not addressed at all.

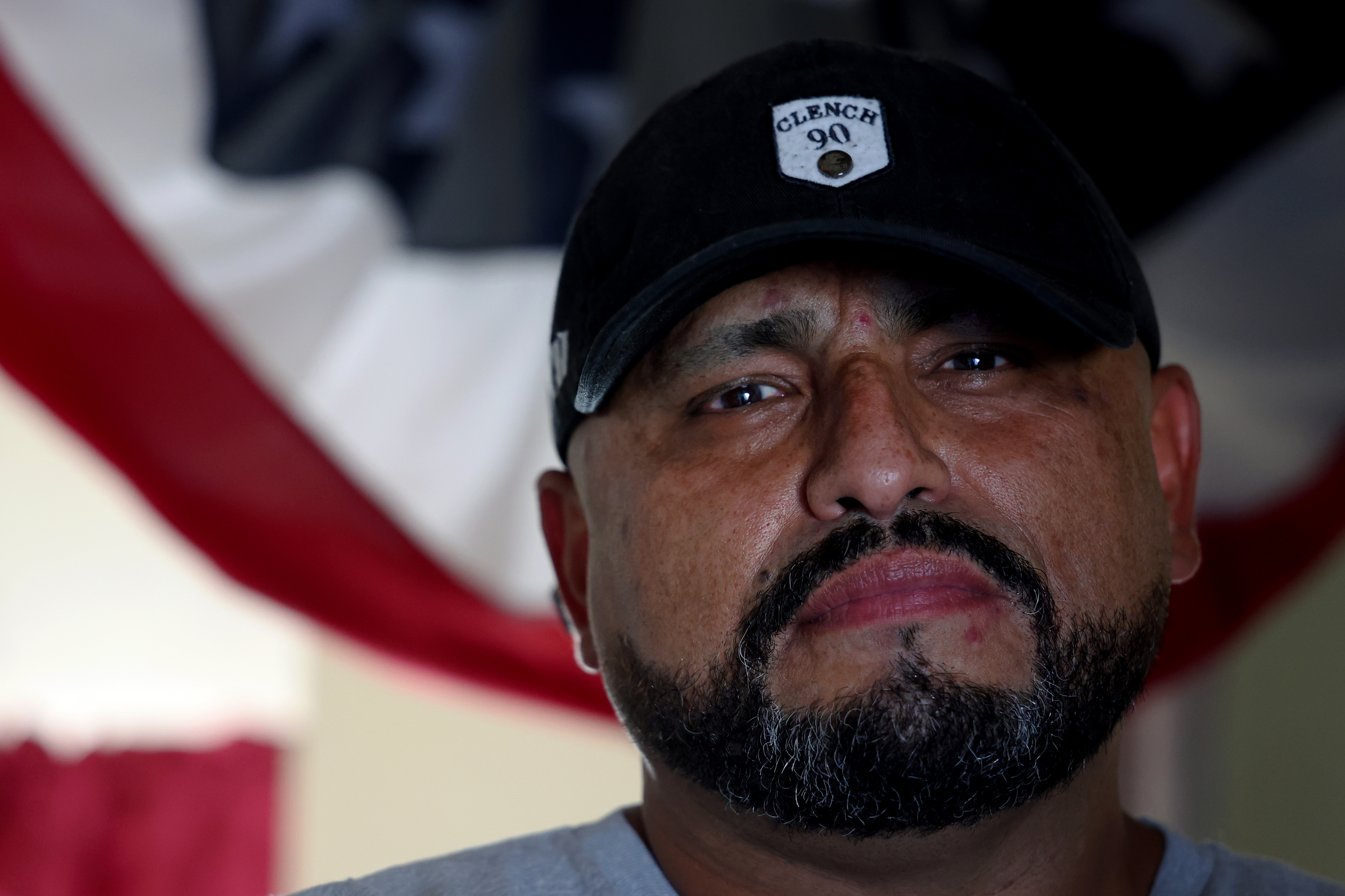

In the wake of all of this, some service members, like Park, are choosing to self-deport. In other instances, immigrant family members of soldiers or veterans have been detained; those include Narciso Barranco, a father of three US Marines who was arrested in Santa Ana, California, while working the landscaping job he had held for three decades.

“Thousands of families like ours are being ripped apart,” Barranco’s son, veteran Alejandro Barranco, testified in July to a US Senate subcommittee on border security. “I want this committee to understand the human impact of the immigration policies of this administration. I want them to know that the people being ripped from our communities are hardworking, honest, patriotic people who are raising America’s teachers, nurses and Marines.

“Deporting them doesn’t just hurt my family,” he added. “It hurts all of us.”

There is no publicly available data on how many veterans are being affected, though ICE is supposed to track removals of service members and veterans and the Department of Homeland Security is typically required to share that information with Congress.

A 2019 federal report found at least 250 veterans had been placed in removal proceedings between 2013 and 2018, with at least 92 ultimately deported. The report said that while ICE had policies for handling cases of noncitizen veterans, it did not consistently identify and track actions against those individuals.

News21 could find only two DHS reports tracking removals of veterans. One, covering the first six months of 2022, said five veterans had been deported; another, for calendar year 2019, said three veterans had been deported.

In June, US Rep. Yassamin Ansari, an Arizona Democrat, and nine other members of Congress wrote to the secretaries of defense, veterans affairs and homeland security seeking the number of veterans currently facing deportation—noting “some estimates” put the overall number of deported veterans at 10,000.

In a news release, Ansari said all veterans “deserve to be treated with dignity and respect, not abandoned by an administration that turns their backs on their sacrifice.” Her office did not return messages from News21. DHS and ICE also did not respond to questions.

In past years, bills to do more to protect immigrant service members and their relatives have been introduced in Congress. One measure, introduced in May, would give green cards to parents of service members and allow those already deported to apply for a visa from abroad. It’s still in committee.

US Sen. Tammy Duckworth, an Illinois Democrat and Army veteran, has proposed several measures related to immigrant service members, but those bills have gone nowhere. Last year, for example, she reintroduced a bill to allow deported veterans who have completed the preliminary naturalization process to attend citizenship interviews at a port of entry, embassy or consulate instead of having to obtain parole to come back into the US. It died in committee.

For Duckworth, deported veterans are not a partisan issue.

“This is about the men and women who wore the uniform of our great nation, many of whom were promised a chance at citizenship by our government in exchange for their service,” she told News21. “It’s about doing the right thing and keeping our nation’s promise.”

‘I wanted to serve this country, this beautiful country’

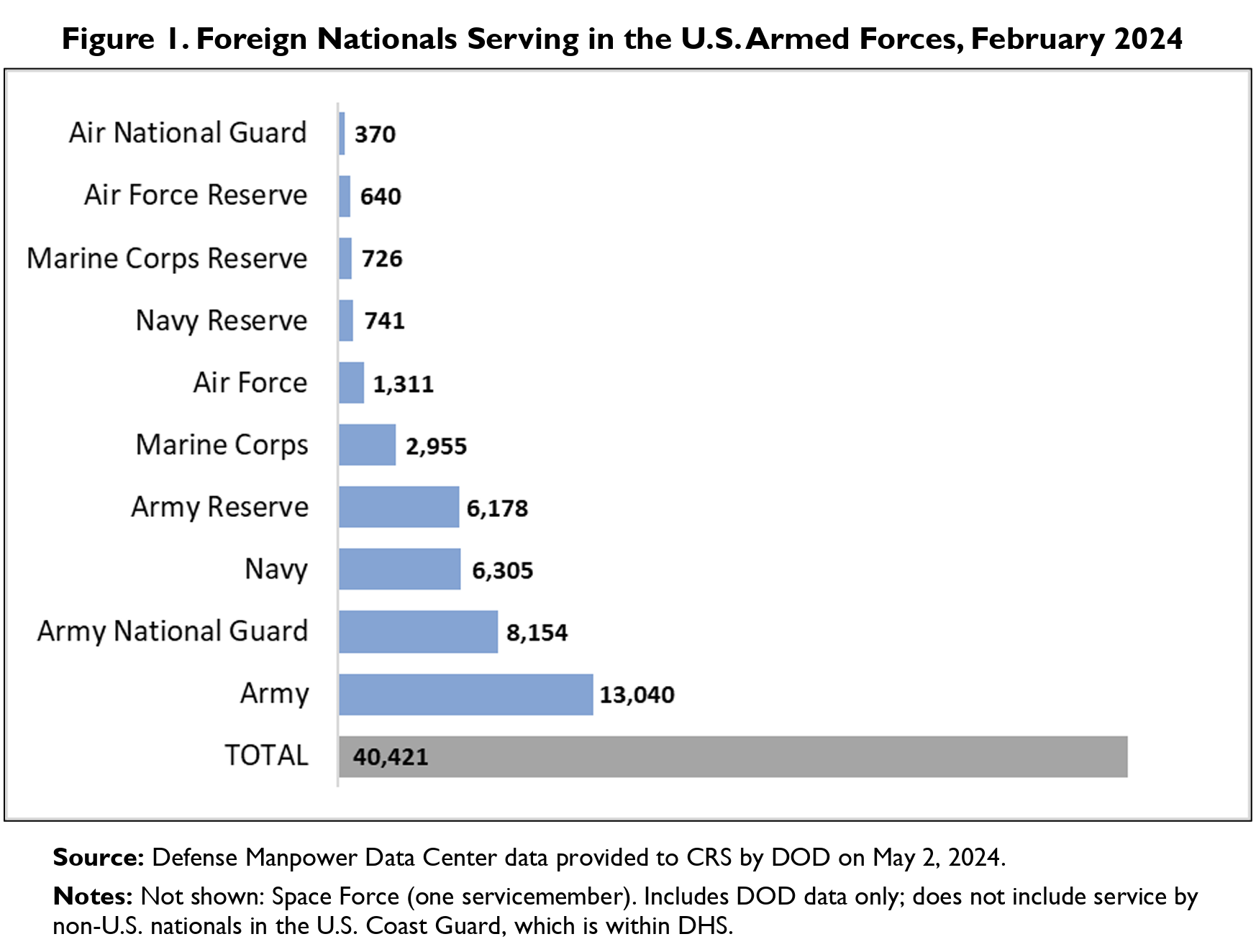

As of February 2024, more than 40,000 foreign nationals were serving in active and reserve components of the Armed Forces, according to the Congressional Research Service. Another 115,000 were veterans living in the US.

Serving in the military has long been a pathway to citizenship, with provisions providing expedited naturalization for noncitizen service members dating back to the Civil War.

During World War I, according to US Citizenship and Immigration Services, foreign-born soldiers made up 18% of the Army. Some units even became known for their immigrant members; for example, the 77th Infantry Division was nicknamed the “Melting Pot Division.”

Since the end of World War I, more than 800,000 people have gained citizenship through military service, according to the CRS report. Since fiscal year 2020, service members from the

Philippines, Jamaica, Mexico, Nigeria and Ghana accounted for over 38% of service member naturalizations.

Generally, noncitizens who are permanent legal residents and who speak, read and write English fluently may join the armed forces. And during designated periods of hostility, noncitizens who serve honorably for any period of time—even one day—are eligible to apply for naturalization if they meet all criteria. The US is still considered to be in a period of hostility because of the post-9/11 war on terrorism.

Despite that longstanding policy, the Department of Defense, during Trump’s first term in office, tried to make it harder for service members to naturalize by forcing them to complete six months—rather than one day—before obtaining the “certification of honorable service” required to apply for citizenship. Naturalization applications subsequently plummeted by 72% from fiscal year 2017 to fiscal year 2018.

The American Civil Liberties Union sued, and in 2020, a federal judge struck down the change.

Plaintiffs, including then-Army Pfc. Ange Samma, celebrated. Samma, originally from Burkina Faso, had lived in the US on a green card since he was a teenager. In 2018, he enlisted in the Army.

“I wanted to serve this country, this beautiful country,” Samma told News21.

Over 14 months, even after he’d been assigned to Camp Humphreys in South Korea, Samma tried over and over to obtain certification of his honorable service—to no avail. He finally became naturalized not long after the 2020 court ruling.

This year, Samma earned his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering. He’s living in Statesboro, Georgia, while hunting for jobs. Because he now has citizenship, “There are many more opportunities that are open for me,” he said. “It’s very rewarding to have it. You feel proud.”

The Biden administration wound up rescinding the six-month policy, according to ACLU attorney Scarlet Kim. As of now, military members can once again apply for naturalization as soon as their service begins.

However, Kim notes, “If you don’t get your citizenship while you’re serving and then you’re discharged, what has happened is that you can potentially become vulnerable to deportation … despite having served our country in the military for however long.”

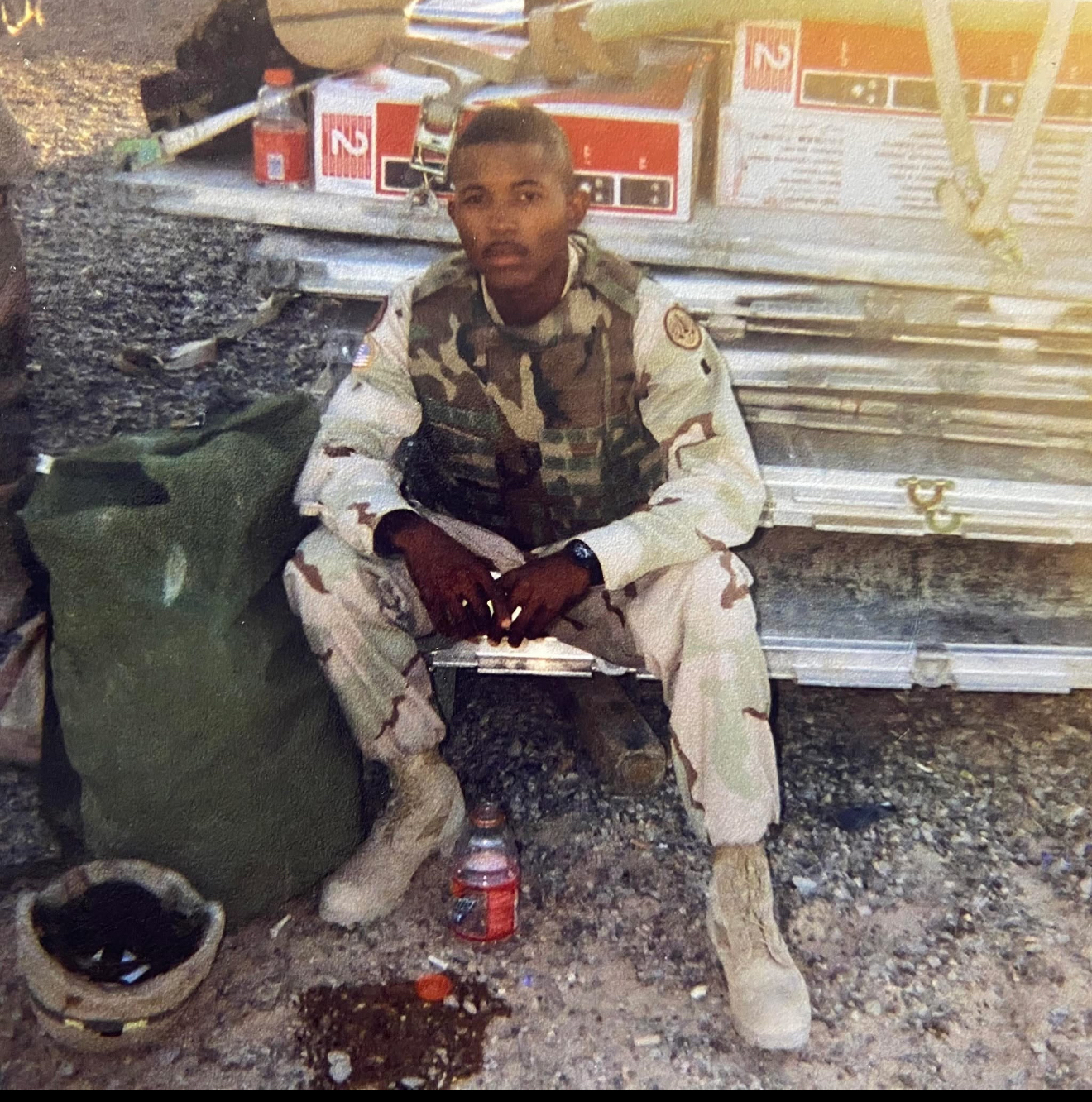

That’s exactly the situation facing Army veteran Marlon Parris.

Parris, who was born in Trinidad, has been in the US with a green card since the 1990s. He served in the Army for six years, including two tours in Iraq, and received the Army Commendation Medal three times, according to records filed in federal court.

Before his discharge in 2007, he was diagnosed with acute post-traumatic stress disorder, which was cited when Parris pleaded guilty in 2011 to conspiracy to distribute cocaine and was sentenced to federal prison.

Upon his release in 2016, he received a letter from the government stating he would not be deported, according to the group Black Deported Veterans of America. But on Jan. 22, just two days after Trump’s inauguration, agents detained Parris near his home in Laveen, outside of Phoenix. In May, a judge ruled that he was eligible for deportation.

His wife, Tanisha Hartwell-Parris, told News21 the couple plan to self-deport and bring along some of the seven children, ranging in age from 8 to 26, who are part of their blended family.

“I’m not going to put my husband in a situation to where he’s going to be a constant target, especially in the country that he fought for,” she said, adding that most people have no idea what immigrant service members face.

“People think that just because you’re a veteran … you should automatically have gotten status as a United States citizen,” she said. But the military, she added, “is different for immigrants. …. You’re fighting the same fight, but it’s not the same battle.”

A report published last year by the Veterans Law Practicum at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law noted the connections between PTSD, criminal behavior and the deportation of noncitizen veterans.

More than 20% of veterans with PTSD also have a substance use disorder, the report found, which can result in more exposure to the criminal justice system.

That situation is “the most common scenario in terms of how deportation is triggered,” said Rose Carmen Goldberg, an expert in veterans law who oversaw completion of the report and now teaches in the Veterans Legal Services Clinic at Yale Law School.

The report also noted that even though deportation does not disqualify veterans from health care and other benefits earned through service, “Geographic and bureaucratic barriers may ultimately stand in the way.”

In 2021, the Biden administration launched the Immigrant Military Members and Veterans Initiative (IMMVI) to ensure deported veterans could access Veterans Affairs benefits. The program offered parole on a case-by-case basis to those needing to return to the US for legal counsel or to access care, and it sought to facilitate naturalization services for immigrant service members.

In the program’s first year, 143 veterans living outside of the US reached out to IMMVI staff, according to congressional testimony. A 2022 story by the nonprofit newsroom The War Horse said 102 veterans had been allowed back to the US via the IMMVI parole program, and “over 30” had obtained citizenship.

In response to questions about the status of the IMMVI program, USCIS directed News21 to its website about the program.

Jennie Pasquarella, a lawyer with the Seattle Clemency Project, said the biggest flaw of the IMMVI program is that parole into the US is temporary – a “dead end” if a veteran doesn’t have a legal claim to restore legal residency or to naturalize.

“We had asked the Biden administration to do more to ensure that there was a further path towards restoring people’s lawful status beyond parole,” she said. “Basically, we didn’t succeed.”

A ‘lifeline’ for deported vets

In the absence of aid in the US, more and more veterans are turning to help elsewhere.

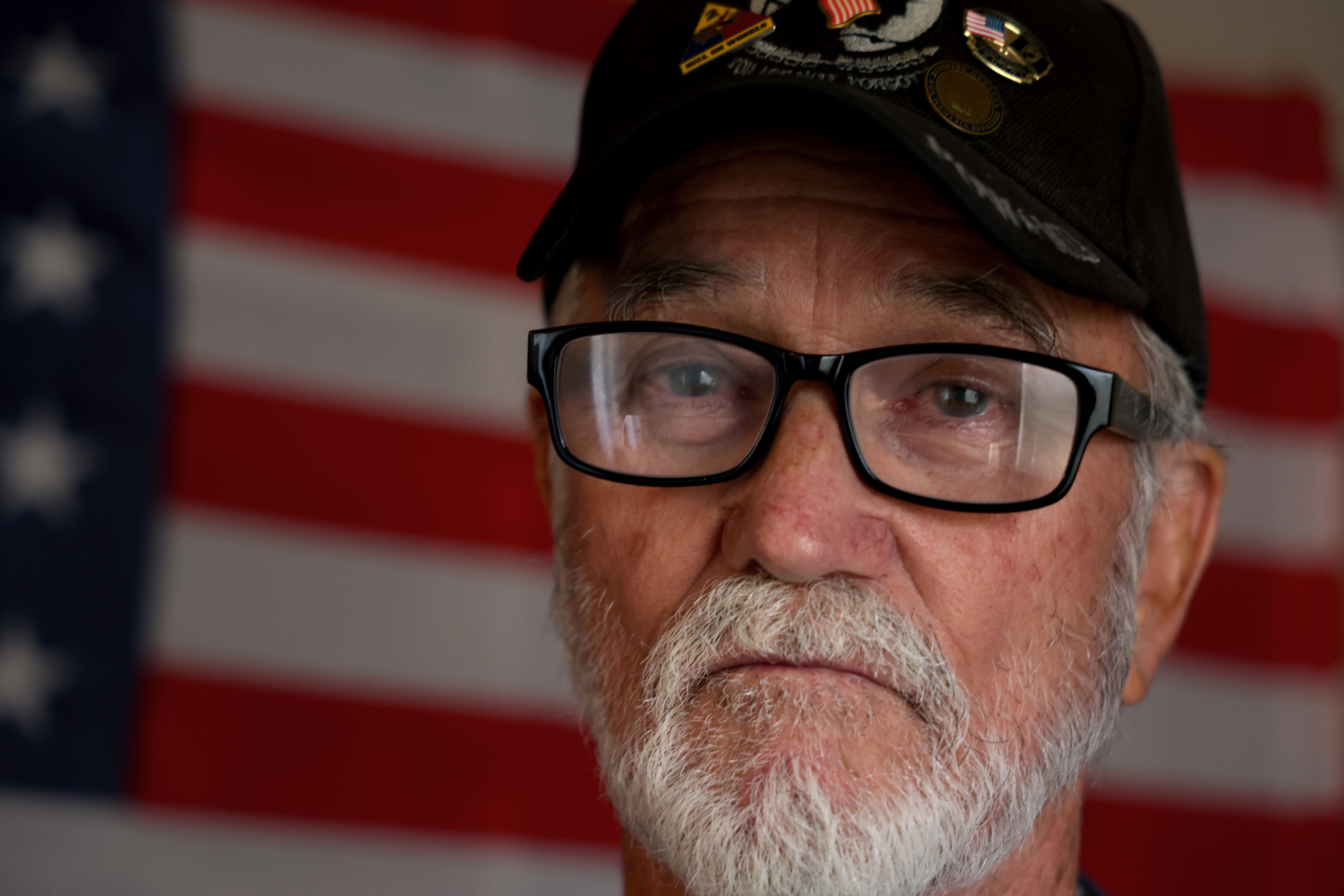

After serving in the Vietnam War with the Army, José Francisco Lopez, a native of Torreón, Mexico, experienced PTSD and struggled with addiction. He eventually went to prison for a drug-related crime and in 2003 was deported back to his home country.

For years, Lopez thought he was the only deported veteran in Mexico—until he met Hector Barajas, a deported Army veteran who in 2013 founded the Deported Veterans Support House in Tijuana.

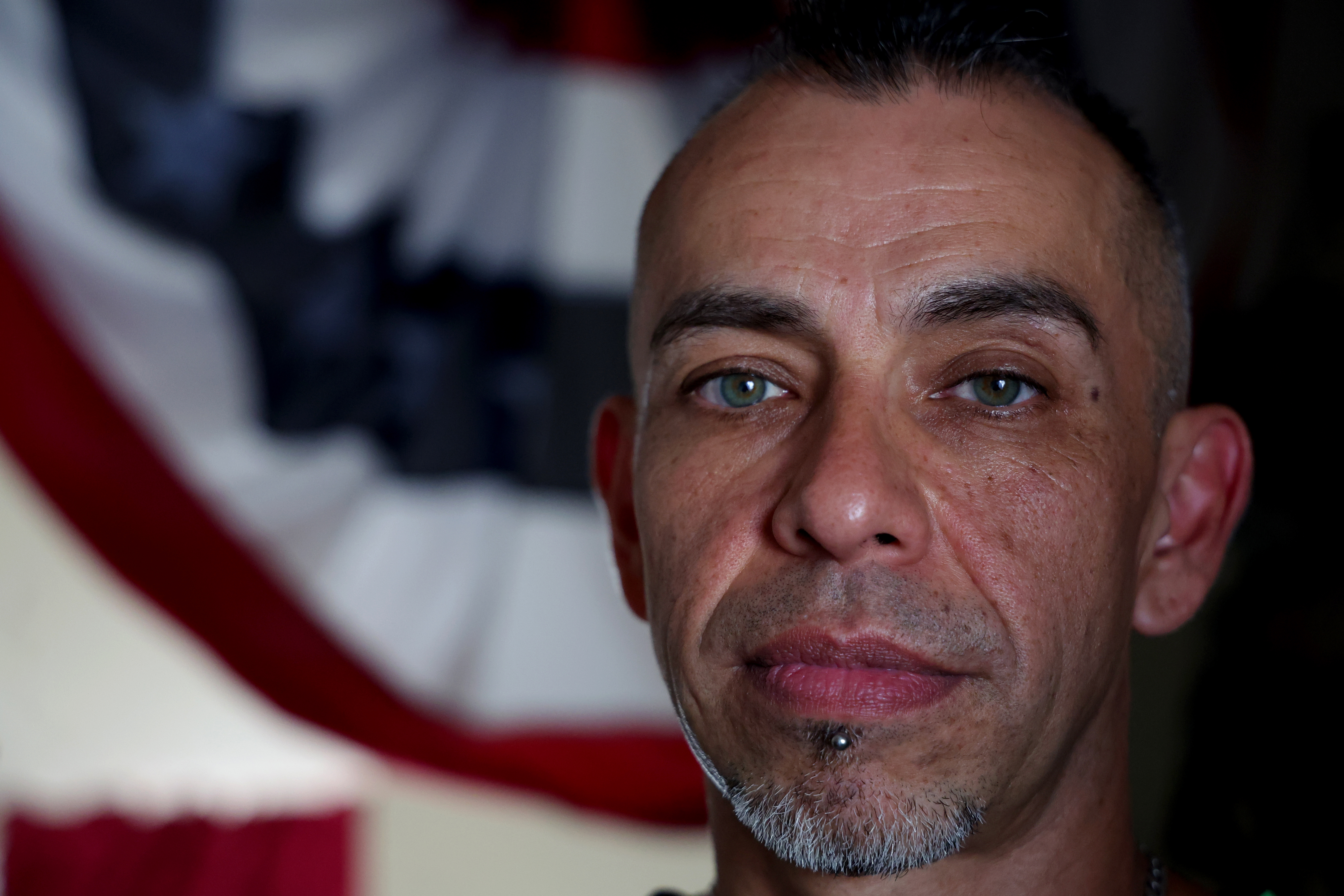

Inspired, Lopez opened his own Deported Veterans Support House in Ciudad Juárez, across the border from El Paso.

Today, Lopez, 80, is a legal resident of the US but splits his time between El Paso and Juárez, providing deported veterans housing, food and advice about how to apply for VA benefits. Since opening the support house in 2017, he’s helped about 20 people.

On a Saturday in June, four veterans stopped by to visit Lopez at the place they call “the bunker.” The gathering felt like a family reunion, with laughter filling the house as they shared memories of holidays spent together and other moments, both good and bad.

Said Ricardo Munoz, who came across Lopez and the bunker in 2019: “It’s kind of like being out in the ocean and someone throws a lifeline at you.”

US Air Force veteran Alfonso, who enlisted in 1976, said he was shocked when he was deported in 2001 after being charged with driving under the influence in El Paso. He said he mistakenly thought he had automatically earned citizenship for serving. Alfonso asked that his last name not be used because he is now trying to naturalize and fears publicity could hurt those efforts.

After living and working in Juarez for decades, Alfonso, with Lopez’s support, obtained parole back to the US in 2024 via the IMMVI program. He got his green card and now lives in El Paso, near his daughter.

For Alfonso, military service was a family affair. His brother served in Vietnam, his niece has done multiple tours in the Middle East, one nephew is in the Coast Guard and another is a Marine.

Citizenship or not, he said, “I was an American already, because I was willing to give my life for it.”

He added, “When you’re willing to give your life for something that, you don’t know, in one second you might be dead—it’s something. It’s important.”

‘It’s a whole new world’

Back in Seoul, Park, 56, is adjusting to life in a country he hadn’t even visited in 30 years. When he first arrived, he said, he cried every morning for hours.

“I just couldn’t stop,” he said. “It’s a whole new world. I speak the language, but I don’t read or write, so I’m trying to really relearn everything.”

For now, he’s staying with his father, but he worries about his family back in the US. His daughter works for the state of California. His son—also a military veteran—lives in Hawaii, where he works in cybersecurity and helps care for Park’s 85-year-old mother.

“I don’t know how many more years she’s got,” Park said. “My daughter, if she ever gets married, I won’t be there for a wedding.”

Park’s attorney started a petition to urge prosecutors to dismiss his criminal convictions, part of an attempt to cancel his deportation order and allow him to return to the United States. More than 10,000 people have signed.

Park said he’s grateful for the support but has little faith that the country he fought for will ever allow him to come back.

“I’m not blaming the military or VA – it’s literally the Trump administration,” he said. “What they’re doing is crazy.

“This is not the country that I volunteered and fought for,” he added. “This is just really wrong.”

News21 reporters Tristan E.M. Leach, Sydney Lovan and Gracyn Thatcher contributed to this story. This report is part of “Upheaval Across America,” an examination of immigration enforcement under the second Trump administration produced by Carnegie-Knight News21. For more stories, visit https://upheaval.news21.com/.