This article was co-published with EdSurge, a nonprofit newsroom that covers education through original journalism and research. Sign up for their newsletters.

A little girl stared at a list of test questions in her science class, unable to answer the majority. Resigned, she wrote at the top, “I failed badly”—although she misspelled it, instead writing, “I felled bedly.”

She was not in a lower-level grade or even elementary school. She was a student of Laurie Lee’s sixth-grade class, more than two decades ago.

Lee never forgot the reading difficulties she witnessed while teaching fifth and sixth graders.

“It becomes clear pretty quickly how they’re struggling,” says Lee, now a senior research associate at the Florida Center for Reading Research. Beyond test scores, she says the struggle was also evident in the questions her students would ask their classmates in response to assigned reading: “It’s often not because of content areas; it’s because they can’t read.”

Lee was not the only education leader grappling with older students’ lack of reading skills. Rebecca Kockler saw similar issues when she worked as the assistant superintendent of academic content at the Louisiana Department of Education. Recently, the state was the second most improved in the nation for fourth-grade reading results, rising from the 50th in 2019 to the 16th in 2025, with high scores measured in 2024. But, despite the strides Kockler’s fourth-grade students were making, it was all but erased by the time they hit eighth grade.

“It was just, ‘What is going on?’” says Kockler, now the executive director at the Advanced Education Research and Development Fund’s Reading Reimagined program. “What was frustrating for me was that I could not touch my middle school reading results.”

According to the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress results, only 30 percent of eighth-grade students are reading at a NAEP “proficient” level. Fourth-grade students had similar scores, at 31 percent. Both fourth and eighth- grade scores were not significantly different from when the data collection first began in 1992.

Many states, similarly to Louisiana, are focusing on deploying research-backed reading programs for their younger students. But, despite a stagnant reading comprehension rate for older students, they are continually left out of the conversation about improving literacy.

“There’s this focus on K-3, without a lot of resources dedicated to helping the kids in secondary school that fell through the cracks.”

“There’s this focus on K-3, without a lot of resources dedicated to helping the kids in secondary school that fell through the cracks,” says Anna Shapiro, associate policy researcher for the Rand Corporation, a nonprofit public policy research firm. “Starting early makes a lot of sense in a lot of ways, but there’s also all these kids in the school system that didn’t benefit from that and do need intervention as well.”

The phrase “science of reading” has cropped up more and more over the last few years. Simply put, it looks into the research behind how one learns the foundations of reading, such as sounding out letters, forming words, and making basic sentence structures.

The research is not particularly new. Congress convened a 14-person panel in 1999, dubbed the National Reading Panel, which submitted a 480-page report in 2000 with its science of reading findings. It found that students need explicit instruction in five pillars of reading: phonics, phonological awareness (or sound structure of spoken words), fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension.

But the last two decades have been dotted with various methods for improving— and teaching—reading skills. There’s phonics, or sounding out the letters of words, which was lauded in the National Reading Panel report. “Whole language” style of reading, which had readers focus on context clues and guess the word that would accurately fit the scenario, was widely popular in the middle of the 20th century, despite not being studied or recommended in the National Reading Panel report.

The modern science of reading push began to inch into the mainstream in 2019, after Mississippi overhauled the way its school systems taught reading starting in 2013—and saw drastic test result improvements six years later, catapulting to No. 9 in the nation for fourth-grade reading skills on the NAEP assessment. The state was number 1 for reading and math gains since 2013. Some dubbed it the “Mississippi Miracle,” with those in the state calling it a “Mississippi Marathon.” It was a model that Louisiana followed quickly after.

Then, the science of reading was flung into the general public’s consciousness with the hit podcast Sold a Story: How Teaching Kids to Read Went So Wrong, which details the history and debates behind teaching children to read.

By 2025, roughly 40 states had passed laws that either mandated or referenced using evidence-based methods for teaching reading, though what that specifically means, and how many resources are actually financially backing those methods, varies from state to state.

Some laws are more detailed than others, with most focusing on “foundational” —or lower-level—grades. Most, if they did specify, target kindergarten through third grades, requiring teachers of those grades to go through the science of reading training, and students that age to undergo screening practices. Others, including laws in North Carolina and Connecticut, expanded those efforts to K-5, with Iowa as a standout requiring personalized reading plans to struggling students through sixth grade. Some states, including New Mexico and Nevada, require all first graders to be screened for dyslexia.

But the change in student outcomes has been slow. According to a new study by EdWeek Research Center, more than half of the 700 polled educators said at least a quarter of their middle and high school students had difficulty with basic reading skills. More than 20 percent said half to three-quarters of their students struggle.

It’s affecting teachers too. According to a 2024 Rand survey, more than a quarter of middle school English teachers reported frequently teaching foundational reading skills like phonics and word recognition—“things that should be mastered in lower grades,” according to Shapiro.

By middle school, the consequences of poor literacy skills pop up across academic disciplines, like in Lee’s middle school science class.

“If they have trouble reading independently, they’ll have problems with other things as well. It’s not just language arts teachers; it impacts everyone,” Shapiro explains.

“If they have trouble reading independently, they’ll have problems with other things as well. It’s not just language arts teachers; it impacts everyone.”

Many reading experts have used the same example: A young child learns to read and understand the word “cat,” but that same child struggles when he gets older and comes across that same set of letters—c-a-t—in new, more complex words like “vacation” and “education.”

“It’s that application into complex words that we basically didn’t teach kids anywhere in our system, in the same explicit way we do with younger kids,” Kockler says.

Ideally, no child would arrive in middle school unable to keep up with his or her assigned reading. Some states are taking efforts to ensure that does not happen, with Louisiana, for example, passing a law in 2023 requiring students to be held back if they do not pass their state reading test unless they qualify for an exemption.

In the interim, though, older students with reading issues are still getting neglected. And researchers are at a loss about how it happens.

“From our research, we don’t really know exactly how these kids are getting to middle and high school and struggling with reading,” Shapiro says of Rand’s findings. “There’s this focus on K-3, without a lot of resources dedicated to helping the kids in secondary school that fell through the cracks.”

Identifying struggling students can be challenging. And there seems to be a major disconnect between what parents think about their children’s literacy skills and the reality. While 88 percent of parents believe their child is reading at grade level, only roughly 30 percent of students fall into that camp, according to a 2023 Gallup poll.

Most older students, once they hit a certain age, read independently—making it difficult for parents to know how well their child is grappling with the content. Meanwhile, some students with poor reading skills are able to cobble together their own tactics to understand assignments and may not be initially flagged as reading below grade level.

For older students who have been flagged as weak readers, there are traditional protocols to offer them additional support. Kevin Smith, who, along with Lee, co-founded the Adolescent Literacy Alliance, says in most schools, struggling students will leave their home classroom to work with a reading interventionist in the day, if the school has one. Other students get more intensive training, focusing on fewer skills for a longer period of time.

The missing piece: Implementing reading strategies in every class, across all grade levels—not just language arts classrooms.

“We can’t intervene our way out of instruction. There’s not enough time in the world to get caught up if they’re not getting help throughout the day.”

“We can’t intervene our way out of instruction,” Smith says. “There’s not enough time in the world to get caught up if they’re not getting help throughout the day.”

Most of that instruction tends to happen in the earlier grades.

“There’s learning to read, then reading to learn,” Tim Rasinki says, quoting an oft-used phrase. He taught middle school students before becoming a reading interventionist. “Even beyond grades three and four, there are still things you need to learn about reading. Critical thinking is a huge thing, but those [reading skills] need to be taught as well. I’m not sure the extent they are.”

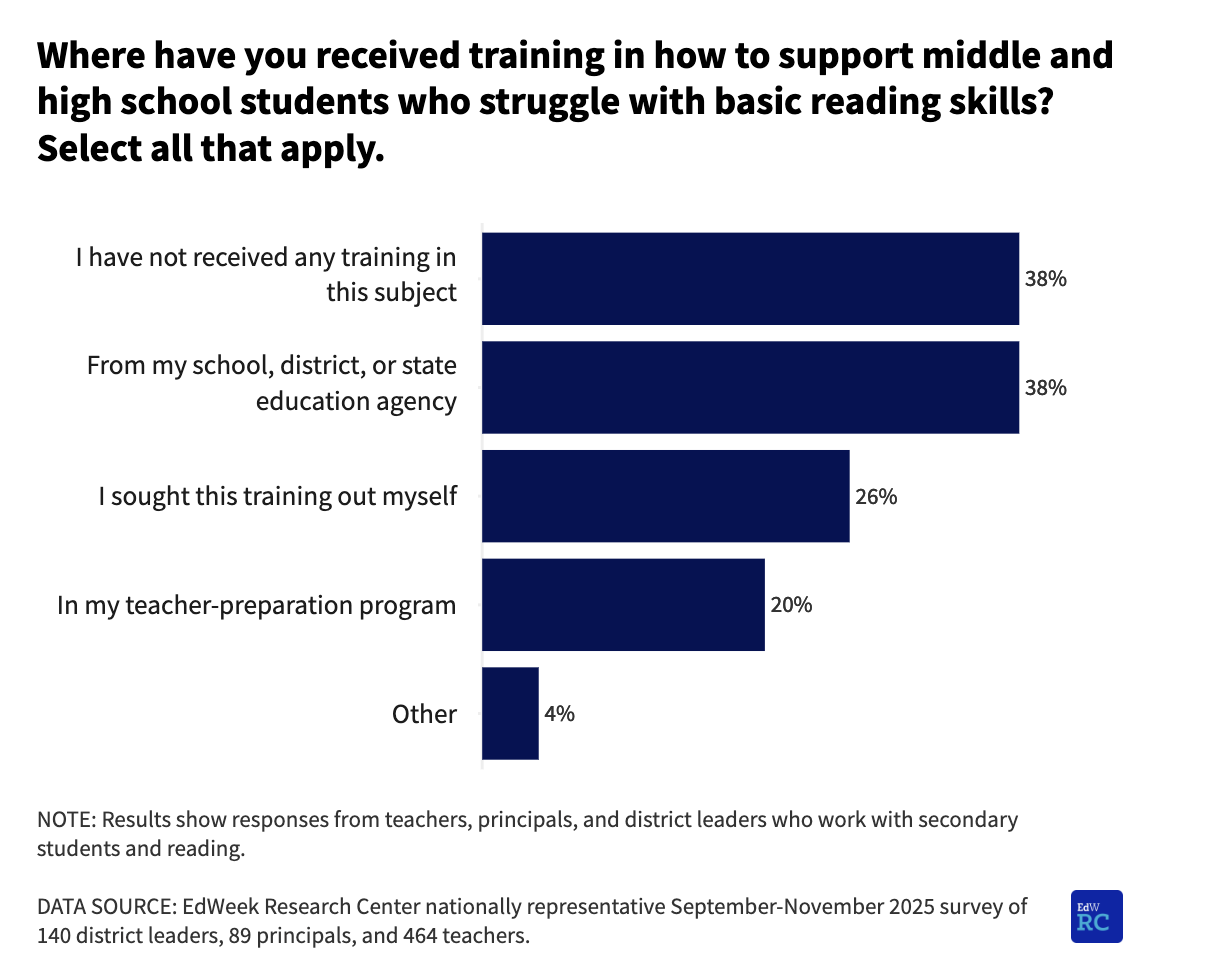

Yet according to the EdWeek survey, 38 percent of educators said they are getting no training in how to handle older students reading below grade level, with roughly a quarter teaching themselves. The remaining 38 percent stated they are receiving training, from either their school, district, or state agency.

Many of the dozens of new state laws explicitly discuss teacher training, with California going so far as to mandate that universities change their teacher training programs. Other organizations, like the Reading Institute, have rolled out a free, 10-hour “Intro to the Science of Reading Course” for all New York City-based teachers.

But, teachers say they have an increasingly loaded plate juggling stressors, including test scores, and keeping curriculum on a set schedule.

As for building in more time for improved literacy teaching, “We’ve heard, ‘Look, Lincoln has to be dead by Christmas; how can we do that?’” Smith says. He advises teachers to focus on implementing evidence-based reading strategies on texts that are most challenging.

Katey Hills, the assistant superintendent for Governor Wentworth Regional School District in New Hampshire, said there was some pushback when her district initially began requiring professional development to teach science of reading techniques. Each of the kindergarten through sixth-grade teachers had to undergo training, along with seventh and eighth-grade English teachers.

“If you’re waiting, you’re a bit behind the times,” she says. “It is a lot of change and change is hard, but it can be done. It’s really important that teachers are trained and you give them the support, but it can be done. Once teachers start seeing the results, it sells itself.”

She recommends creating a task force to hear from teachers on the best adaptations for the material.

The district just put the program into place widely last year, but already, one first- grade classroom is 100 percent literate.

Meanwhile, Lee and Kockler both say they are optimistic about the future of literacy for older students.

“Mississippi and Louisiana are incredible examples of when you have good research and tools to deploy, you can see real results,” Kockler says, adding that the next step is to get more clarity and better tools focused on helping older children’s literacy. “I feel very hopeful. But there’s a lot of work to do, for sure.”